One of America’s first board games was the Walk of Fame

Like today’s fitness promoters, celebrity walkers have used their platform to make money, gain fame, and exchange travel. Edward Payson Weston attempted to walk 500 miles in six days.

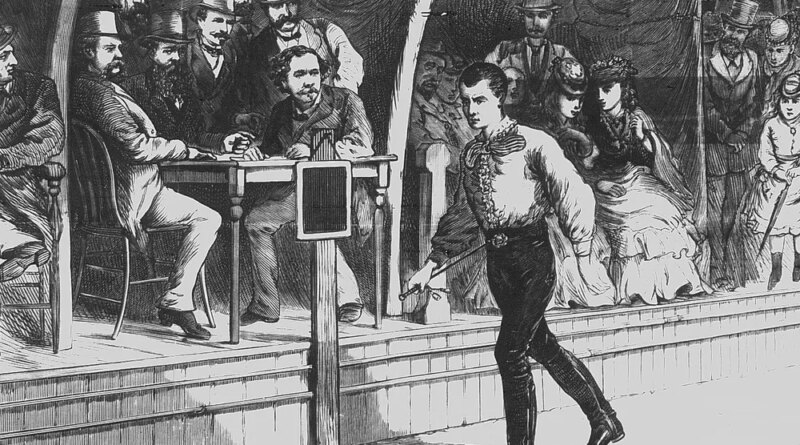

Frank Leslie’s Comparative Journal / Public Domain

Walking does not require a social worker. The easiest, most accessible form of exercise has been around since people first started looking for and walking on the ground.

But today, walking seems to have entered its heyday.

It has been the subject of many viral videos, of people doing it quietly, in general, for their mental health, for their physical health, for “hot” reasons. girl” and, yes, even for their stomach needs.

However, there is more to these little trends than gym goers looking to make a quick buck on brand name water bottles or $30 socks. A new wave of fitness enthusiasts—many of whom are women of color, of different body types—seems to be reaching that audience, thanks to a number of factors from safety to in the areas of administrative discrimination, those who have avoided leisure work. This is reflected in the explosion of walking groups in the United States in recent years, with topic after topic describing the rise of these gatherings across the country, which has inspired hundreds of people who have not who know that they get together every week for training.

It is not the first time that a different group of promoters has expanded the walking distance. In the 1870s and 1880s, an unlikely group of Americans became some of the first public figures in the rise of the pedestrian movement.

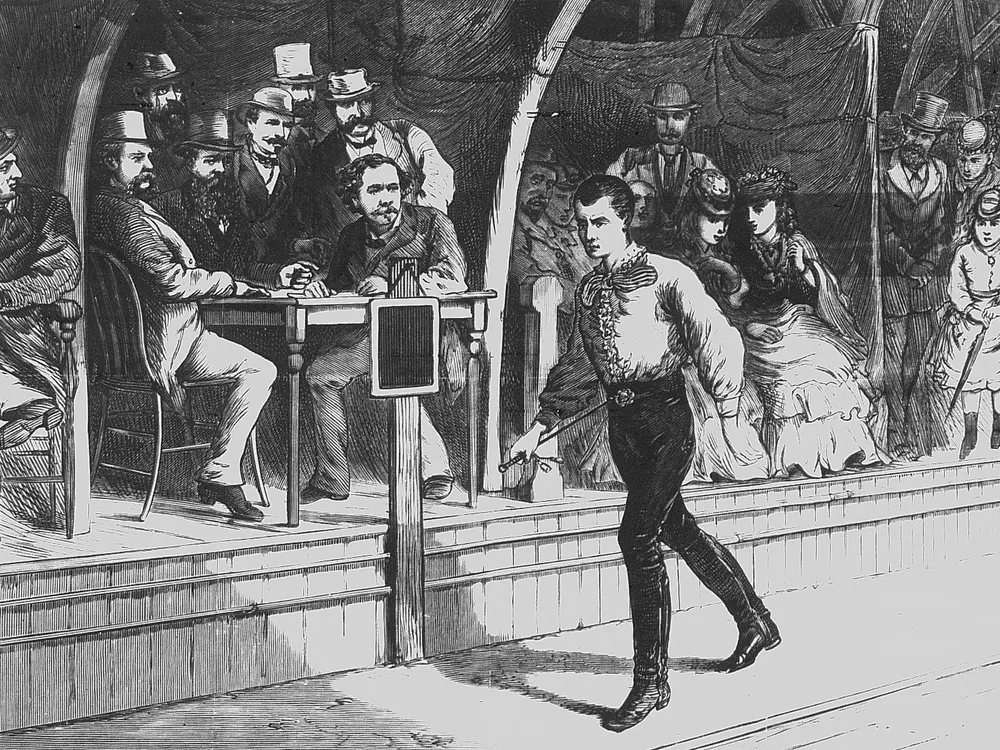

These elite hikers traveled hundreds of miles, off-road and cross-country, to compete in one of the nation’s premier spectator sports. Although the craze was short-lived, it left a legacy that challenges the face of morality even today.

American footmanship began with a bad bet: In 1860, door-to-door book seller Edward Payson Weston bet a friend that Abraham Lincoln would lose the upcoming presidential election. If Lincoln won, Weston announced, he would travel 478 miles from his home in Boston to Washington, DC for the inauguration – and he would do so in about less than ten days.

After Lincoln’s victory, Weston set out to fulfill his promise, publicizing his march in local papers along the Eastern Seaboard. People stood for hours in the cold to watch him pass through their villages. The runner and debt collector left Weston 4 hours and 12 minutes to reach his goal; Lincoln, who was following his progress along with the rest of the country, was still so impressed with the work that he offered to pay a latecomer. (The savvy Weston hesitated, apparently knowing that refusing would get him more protection.)

After the Civil War, Weston took his show on the road. Thousands of spectators lined up to buy tickets and bet on whether or not he could beat the clock. In a divided country, his departure was a unifying event. “He’s very political, and I think that’s helped his popularity,” Matthew Algeo, the author of Walking: When Watching People Walk Was America’s Favorite Gamehe told me in an interview. He could go anywhere and walk, and people would not object to that.

Walking wasn’t a popular form of exercise in the US when Weston started doing his shows, but he and the competitors who stood up to challenge him spread “walking fever” among the public. “Plea for Pedestrianism,” published in New York Times in 1878, it was a common mode of transportation. Readers provided examples of walking around Staten Island, recommended clothing (“soft, but sturdy, boots with wide soles and low heels”), what to eat (“sandwich and eggs hard-boiled. in your pockets”), and how to prepare (“Those who are not used to walking a lot should practice this moderately during the week before walking all day in the country”).

Celebrities, long reserved for royals and politicians, were on the rise—allowing peds, or “peds,” to have real influence. and some of the country’s top selling stars. They used their platform to promote not only the game, but also everything from sneakers to business cards. They were even the first to sell advertising space on their competition apparel.

One of the reasons why so many people were affected by footy, Algeo suggested, was that these athletes took on a sport that could be associated with it—an “everyday show”— and they push it to extremes. He said the result struck people as “personal,” “real” and “real.”

The best hikers showed up in the American crowd, too. Because these travel games were largely unregulated, there were no clear rules that excluded certain teams from the competition. One of Weston’s rivals was Daniel O’Leary, an Irish immigrant who became the “Champion Pedestrian of the World” in 1875 after defeating Weston in a six-day race. O’Leary took many athletes under his wing, including Frank Hart (born Fred Hichborn), a Haitian immigrant. Hart became one of the sport’s top stars and the winner of the second O’Leary Belt in 1880, earning more than $21,000, the equivalent of two-thirds of a million in today’s dollars. .

Women “walkers” also had a big impact on the sport. At a time when mainstream science believed that intense athletics were permanently damaging women’s bodies, draining them of their “vital energy” and reproductive potential, athletes like the English woman Ada Anderson stood as strong examples, showing what sportswomen could do. .

“It’s good for women to see how much a woman can endure,” Anderson said New York Sun in 1878.

But there was a negative side to women’s walking. The game was largely promoted and organized by men (including one of PT Barnum’s public relations people). Many women come to professionals out of desperation, to escape poverty or abusive relationships. Then they pushed their bodies to the limit. They did what men did—walk for 24 hours, walk 100 kilometers, walk for six days—but they also tried to do extreme things, like walking 3,000 kilometers during 3,000 hours.

“This was a very difficult life,” Harry Hall, author of The Pedestrianshe told me. He said the women were walking in hard shoes, because the saboteurs threw stones, pins and glass in their path, hoping to fix the results of the race.

The same laissez-faire approach that allowed the sport to evolve has also led to similar abuses and scandals. The footy management saw race fixing, the first use of steroids and an attempted robbery which resulted in the manager taking his own life. With the rise of bicycle racing in the 1880s, society moved on, leaving footmanship to fade into a footnote.

“There was no way the hike was going to last forever,” Algeo said. But it’s sad that it killed itself.

Today’s travel influencers have different goals and objectives, not to mention more organizations, than the sports stars of a century and a half ago. But both waves can be seen as encouraging “physical activity in areas that have not been traditionally or easily done in the past,” according to Damon Swift, an exercise expert at the University of Virginia School of Education and Human Development, he said. me.

For those who want to catch this trend today but aren’t ready to count 10,000 daily steps – let alone a trip from Boston to Washington – you can find wisdom in 1878. Times trend story, which reminded readers to “walk for a long time [one] love.”

Do just that, it promised, and you’ll go home “healthier” and “happier.”

#Americas #board #games #Walk #Fame